2,374 words

A Moment of Unexpected Clarity

One does not look for moments of clarity while trying to play a video game. The medium is one that has been greatly diminished in my house due to time and choosing to spend one’s time on forms of entertainment that are more informative and, to put it bluntly, written better. This is not the fault of the talented writers tasked with bringing these games to life. There are essential mechanisms, such as pacing, that they cannot control and market forces which dictate what they can accomplish. There have been titles in the recent past with exemplary writing that had warranted attention. Ninja Theory’s Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice chronicled postpartum depression and psychosis and how it was viewed in the 8th century. CD Project Red’s The Witcher 3 took the entirely mediocre series of books of Andrzej Sapkpowski and made a masterpiece. Respawn Entertainment’s Jedi Fallen Order handled the typical campy, shallow and family-friendly Star Wars franchise and produced an experience that was worthy of setting aside one’s Kindle.

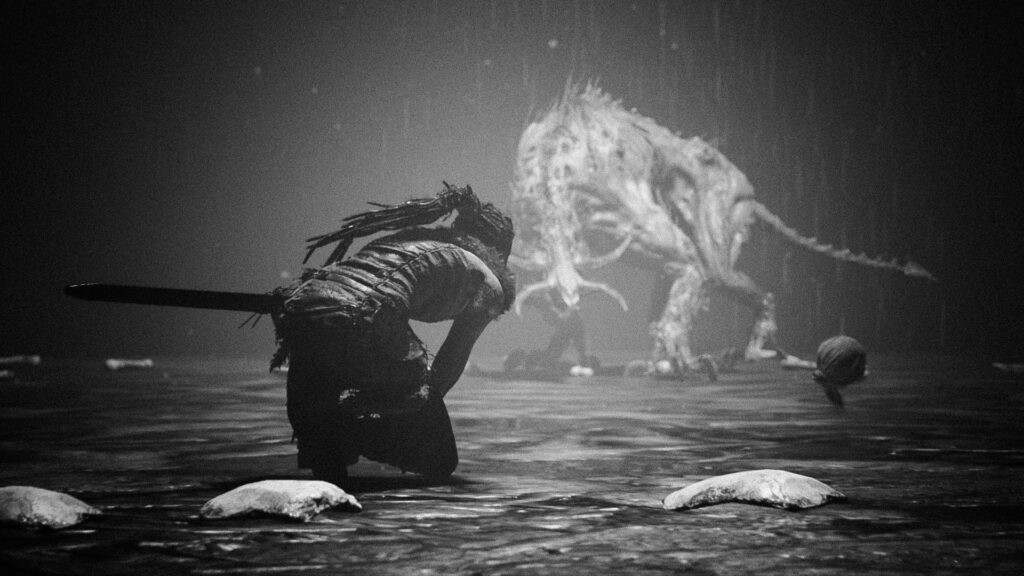

A promising title, now a series, Hellblade tackles complex matters without ever diminishing the humanity of those on screen.

Though one does not look for moments of clarity when holding a video game controller in their hands, that is exactly what I experienced a few hours into the long-awaited sequel to Star Wars Fallen Order, Jedi Survivor. Incredibly, this moment of clarity was reinforced a few days later when I played another game, and the contrast of the two offered insight as to what is wrong with the medium of gaming.

A rare moment of clarity of what is wrong with the medium of gaming came as your character stumbles upon a recently crashed enemy ship.

The Agency for Mercy

The first moment of clarity came a few hours into the campaign of Jedi Survivor. Already having killed hundreds of “enemies” in the form of Storm Troopers, my main character came across a crashed enemy ship. All evidence provided to the player indicated that the crash had happened quite recently. When I turned the corner and saw the flames that were engulfing the ship, I immediately ran to it and looked for survivors. There were none to be found. Instead, the developers had decided to hide a cosmetic upgrade behind the crashed ship. At this moment, I stopped, looked at the wreckage, and then turned off my video game console. The fact that I had stumbled on this scene and was then expected to continue to play a game where I killed endless waves of “enemies” was something that I was not equipped for. To not have the option to help those in need, regardless of whether they were an adversary, was not something I was willing to accept. This highlighted one of the reasons why I stopped playing video games frequently a few years ago. I mentioned this in a light-hearted manner to some of my friends who still play video games frequently, and I did not think much of it until a week later.

With different pacing, mechanics, and a higher priority on writing, narrative titles such as Star Trek Resurgence offer consumers an option with excellent writing, but not without a cost.

This distinct lack of agency to show an opposing side any mercy or kindness was contrasted with the title Star Trek Resurgence. Multiple times throughout the story, the characters you control can put themselves and those they oversee at risk to save those who do not belong in their “us” group. By extending a hand of kindness to the adversarial “them” on multiple occasions, this title not only gives the player this agency but also explores the consequences of choosing whether to do so. However, these two games are quite different in terms of mechanics, and this may lead one to leave this as reason enough to leave the matter alone, but I’d argue that the intent and the writing itself allowed for this.

Mechanics Are Partly to Blame

As mentioned earlier, there are certain mechanisms that writers cannot control in most forms of video games, and not all video games are alike. Jedi Survivor is a third-person action-adventure game which focuses on fast-paced combat and platforming puzzles to entertain the player until the next milestone in the plot. Star Trek Resurgence is a slow-paced dialogue-driven narrative adventure and thus affords exponentially more flexibility and opportunities for writers.

Several times throughout Resurgence’s plot, the player is confronted with the decision to put their own crew at risk for others. In one scenario, the “them” group were not adversaries but simply a group you were not aligned with. Later you are essentially given the same opportunity to show mercy and save a group that are a ruthless adversary. The beautiful aspect of Resolute is that there are consequences as to whether you show mercy or not. Members of your crew may resign from Starfleet (think of it as someone quitting their career in the armed forces), as they did in my playthrough because I had decided to show mercy to those who would not ever return such a favour.

The fast-paced gameplay of Survivor and combat does not allow for many opportunities for mercy, save for one instance. Slightly hidden away at the top of a tower which becomes accessible near the third and final act of the game, the writers and programmers showed a degree of awareness about this issue. Once you make your way to the top of the tower, a boss battle commences, but not a normal boss battle. Boss battles are conflicts with much stronger enemies and are usually tied to the plot in some manner. In Survivor, a giant red health bar fills up the top of the screen, along with aggressive music to announce that such an encounter has started. However, in this tower is a normal soldier who can be dispensed with a single strike. The combination of the visual and audio cues sends the player into a defensive frenzy, usually killing this normal soldier instantly. This soldier’s name is “Rick the Door Technician,” and his placement in the game is not just funny but poignant commentary.

Placing the player in the specific scenario where they are stumbling in on someone’s workday and murdering them simply to progress through the game shows tremendous awareness and empathy from the staff behind the decision to include this. Being forced to remove the humanity and worth of a life in a video game by categorizing the sentient enemy as a Storm Trooper or the many variants of wildlife in the game as feral species which attack you on command can be taxing. This is especially true when an enemy is placed between the player and their objective.

On multiple occasions, the Mass Effect series has used brainwashing or genetic manipulation of characters to strip them of their humanity.

Most video game series get around this by creating enemy templates which the gamer can immediately identify and act accordingly toward, usually with violence. The Fallout series uses bandits and various humanoid creatures such as super mutants or ghouls. The Fallout series slowly strips away the humanity from the ghouls, who were once sentient humans, as they slowly become feral over time due to radiation exposure. Space operas such as the Mass Effect series use space pirates or mercenary groups. The Mass Effect series also stripped humanity from characters through genetic terraforming or brainwashing. This would create an enemy which was ruthless and thus easier to kill while playing the game. Cyberpunk uses gangs which are identifiable through colours and body language. Fantasy series such as the Witcher series also use bandits. In almost all of them, there is a small mission where the player encounters a character who belongs to one of these groups yet doesn’t quite belong somehow. The player is then usually given the choice to help them leave the group or to leave them to their doom in the violent group.

Fantasy series such as The Witcher or The Elder Scrolls navigate one’s potential empathy for enemies by simply branding them as bandits.

At one point, quite early in the game, the experience had taken its toll on me. “I still do my best not to kill Storm Troopers in this game, for I feel bad for them being soldiers on the wrong side,” I wrote to a group of my friends in a group chat focusing on video games. “And I’m not a fan of the game hiding rewards behind a giant beast who was just having a day, being a happy giant fur ball, being cute and all… until I come in and ruin its day and thus creating generational trauma for all of her kids to have it happen again during the next enemy respawn cycle. Is this game going to force me to go to therapy?”

Hellblade turns the focus on the main character herself, her psychosis, and her fleeting grasp on reality and her own humanity.

There are many examples within this medium where mercy can be shown to adversaries, such as the “Hitman” series, where the player is given the choice to incapacitate those in the way of his primary target. Given the available buttons and control layouts, implementing such mechanics into games that push the player’s skills and reaction times is next to impossible. Unfortunately, these examples are few for the audience at large does not demand them, and this disproportionately impacts the landscape.

The Incentive for Mercy is Absent

In 2013, Evan Williams, the co-founder of Twitter, spoke about how to make an online product or service effective in gaining the market share of a population’s attention. The two factors that he mentioned were speed and cognitive ease. This factors into all products and experiences, not just those found online. The term that is used for this kind of consumption is usually prefaced with the word “comfort.” Common examples are comfort food and comfort viewing. Comfort food usually being something easily prepared that also delivers a lot of calories such as pizza or ice cream. Comfort viewing examples are reality television or sitcoms that have laugh tracks. The laugh tracks remove any cognitive effort on the audience’s part to try to decipher, or in most cases, even bother to understand, the delivered jokes. Any activity with the prefix “comfort” thrown in front of it requires minimal effort in terms of consumption. All mediums cater to comfort consumption, especially for releases that are in the blockbuster category. Both films and video games can take years to make, requiring staff numbers to reach four figures. The level of investment required to make a video game such as Star Wars Jedi Survivor or any of the Marvel movies applies pressure for a maximum return.

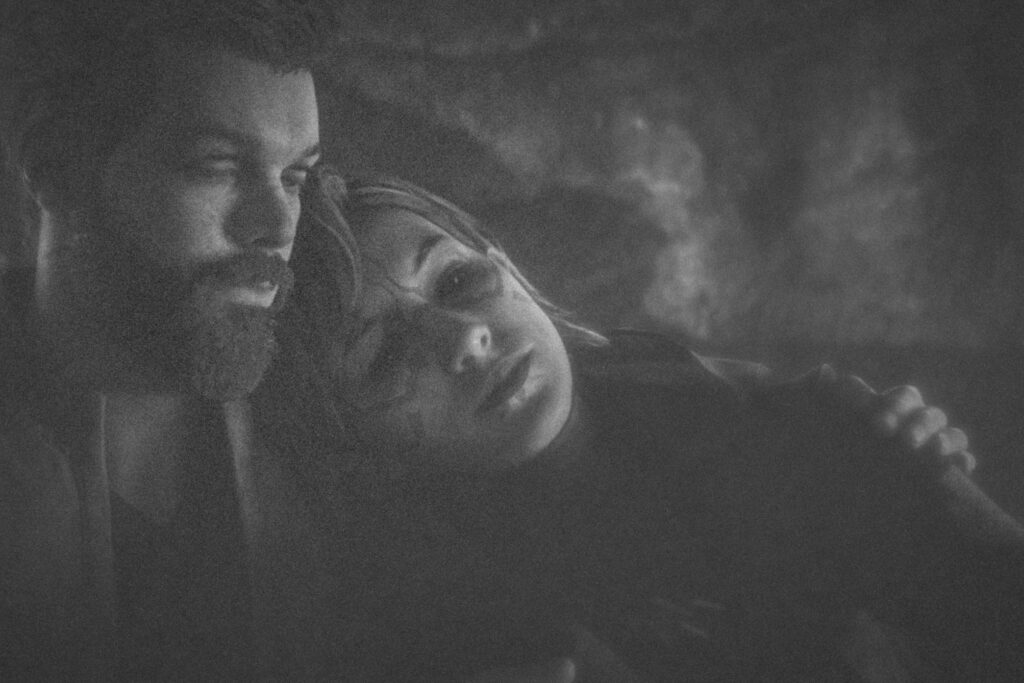

Though used as an example of what is wrong in the industry, Jedi Survivor stands out for outstanding character development, relationships, and the main character’s battle to hold on to their humanity.

However, the consequences of comfort products overtaking various industries greatly impacts the field of video games like no other. Television shows or movies which are made to cater to the widest audience possible typically sacrifice deep character development, and the writing is made to be easily interpreted by various audiences. This is not too big an issue in these fields, for there are enough large production studios willing to undertake projects that are not as commercially successful. Smaller Indie studios exist in both the gaming and movie industries, but the manner in which the video game is built and developed leaves it at a great disadvantage in comparison. The issue with the video game industry is that there are not that many large developers, and there are not many people who were once talent (programmers in gaming versus actors in the film industry) who, through their success, become producers of passion projects, which does not have the return on their investment as the primary goal. The only example which comes to mind is Tim Schafer and his Double Fine Studios, which Microsoft now owns. The result is that most triple-A (the term used to describe the largest productions) have thin and shallow writing to cater to the widest audience possible. Most barely have any writing at all, for the primary concern is keeping the player playing as long as possible so that they will spend more money while playing.

There are large productions such as Destiny, and they all deploy an extremely vague form of writing with next to no character development. They all share extreme stakes at the centre of the plot and how you’re just thrown into the middle of a world or even galactic-saving scenario.

Star Trek Resurgence was a far smaller production when compared to Star Wars Jedi Survivor, and it showed on many fronts. The game’s graphics were more primitive, and the length of the game was far shorter – around ten hours versus a hundred. Games with large production values that barely have any writing, such as Call of Duty, Destiny and Fortnite, populate the market. This leaves consumers who value good writing to look elsewhere, for good examples are far and few between. Games with good writing can be slower-paced and often will require a more complex control mechanism due to implementing more agency for the player. This makes the game slower and requires more cognitive effort from the consumer, thus, making it a far riskier investment.

So Where Does This Leave Us?

Consumers looking for video games that prioritize writing and addressing the full array of consequences within the game will have to look hard for such titles. Furthermore, they will have to look at places that they are not used to. Since such games will not be the big releases which have the marketing budgets that make it easier to discover them, the best example at the time of writing is the release of Diablo IV and all of the commercials and billboards; gamers will have to search harder. They may have to give up on consoles and only play on PC, for a lot of these smaller titles are not ported to consoles due to the costs of doing so. Once again, this extensive search is a slow process that requires effort. Thus, it is all too easy to give up on the industry and pick up one’s Kindle, not the video game controller.

Beautifully written, for the most part, Fallout 4 and those that preceded it, this game uses simplified tropes in grouping enemies into inhumane beings that occupy the world.

The effort can be worth it, but sadly as history has proven, the examples will be few and far between. This period of the gaming industry is considered to have followed a golden era where there were many games released with great writing and gameplay. Now the emphasis is on generating money through micro-transactions, and compelling writing has fallen in priority. The discerning must not be discouraged by the current landscape, but they should also not buy games that they know will disappoint them. Discerning gamers do not occupy a large enough of the market to make a difference with their purchasing decisions, but at least your time will not be wasted. Unfortunately, this means that the medium of gaming is and will remain a secondary option for entertainment. It is disappointing that an entire industry’s products have to rely on mechanisms that incapacitate the value of life and humanity, which is not acceptable for many people, and nor should it be.

The endgame experience of Jedi Survivor shows the great attention given to writing. The lead character can stumble into multiple environmental storytelling elements that illuminate the traumatic journey that he experienced.