Introduction

As the young woman prepared for her testimony at the UN Security Council on that December day in 2015, she first had to wait for the applause to settle. “I’ve been to a lot of Security Council meetings, and people don’t clap,” said Samantha Power, the former United States ambassador to the United Nations. “But they’re clapping for a remarkable young woman.” Mrs. Power has met a lot of remarkable people in her life and has written about them. When she proclaimed someone to be of note and deserving of attention, those in attendance listened.

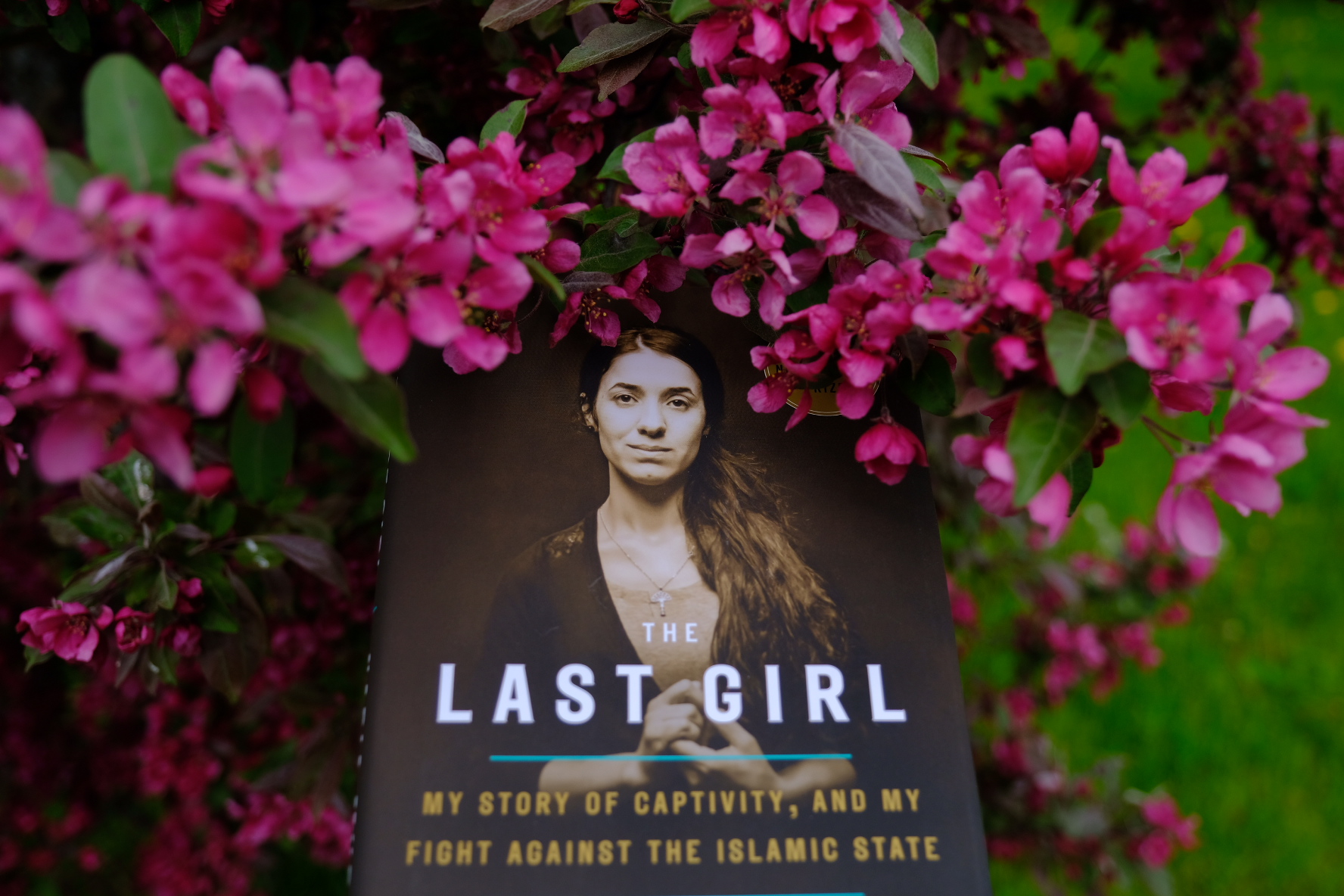

That young woman who testified that day about the horrific Yazidi genocide at the hands of the Islamic State was Nadia Murad. Ms. Murad’s recalling of her own and her people’s nightmare left those in the room in tears, and the soon-to-be decorated United Nations Goodwill Ambassador for the Dignity of Survivors of Human Trafficking, and Nobel Peace Prize winner, would continue to do so for the next four years.

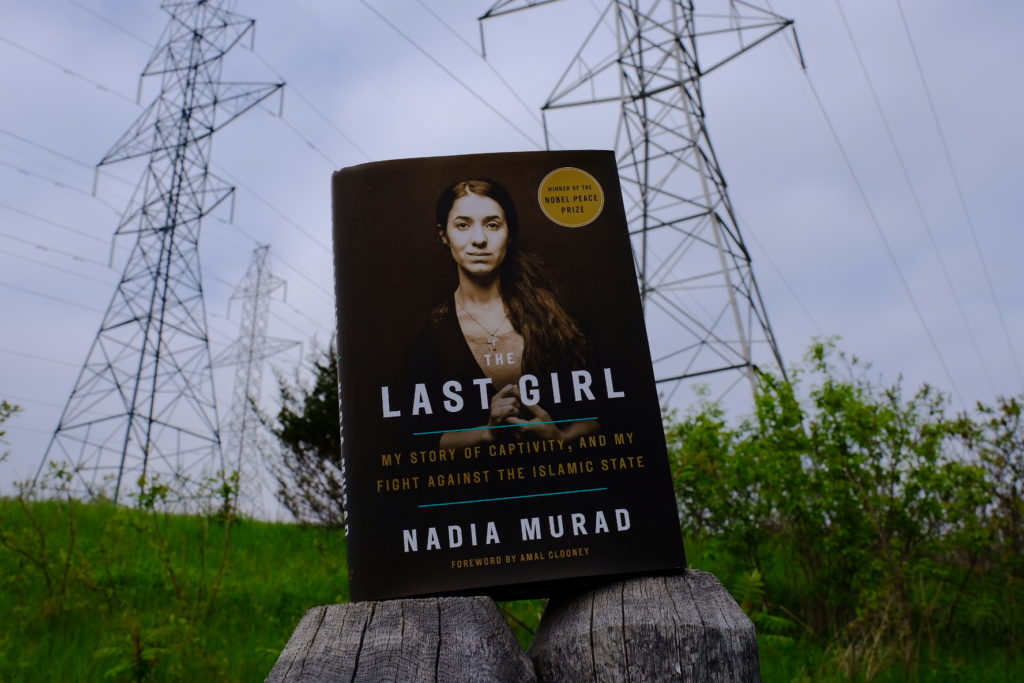

Previously we looked at the works of Alexis Okeowo in A Moonless Starless Sky, and that of Dunya Mikhail in The Beekeeper. With those book reviews we went over religious extremism and how it fosters terrifying killings and horrendous use of human trafficking, but through the lens of a journalist or a writer. With The Last Girl we shall take a look at the account of a victim in her own words. Furthermore, this book review will focus on her people, the Yazidi, and their struggles since the genocide in 2014.

The Yazidi People

Located in northwestern Iraq south of a hundred-kilometre line of mountains is Sinjar, the home of the Yazidi people. Located east of the Syrian border, the Yazidi had continuously seen discrimination and violence at the hands of their neighbours. Yet due to their nature, whether this was with their neighbouring Sunni Muslims or Kurds, they still kept close relationships with those who lived nearby. Yazidism is a monotheist religion that has been repeatedly misinterpreted by outsiders, and these misinterpretations were used as false justifications to subject the Yazidi to discrimination and violence.

The key point which is misinterpreted is the Yazidi belief in the angel named Tawûses Melek, who according to their belief system was the leader of the archangels, not a disgraced and fallen angel. Yazidi worship Tawûses Melek as the peacock angel who did not bow to other things. The other six angels were then created after him. After God created Adam and told the angels to bow to Adam, Tawûses Melek would not. Thus, some Muslim groups saw a parallel between Tawûses Melek and their own Satan. As a result, neighbouring Sunni Muslims used this as an excuse to conveniently label the Yazidi as devil worshippers.

Since the Ottoman Empire, the Yazidi had seen discrimination and persecution and were killed. After the downfall of Saddam Hussein’s regime and the Iraq invasion came the worst period for the Yazidi.

The Book

We are introduced to Nadia Murad, her people in the village of Kocho in Sinjar, and their daily lives. We learn about their daily concerns, and their relationships with other neighbouring groups. Most importantly, she gives a window into life before the tragic events of the siege by ISIS. We are introduced to Nadia’s family: her wonderful mother and her relationship with her father, her siblings, and her cousins, nephews, and nieces. The life they led in Kocho was one of hard work living off the land, and just like that of lives led everywhere else. This was a life filled with joy and sorrow. Nadia wanted to become a hair stylist when she grew up, for she “wanted women and girls to see themselves as something special.” The Sinjar region was one of hopes and dreams, filled with people who worked hard to make them come true. They were never dissuaded by the region’s instability.

The Iraq invasion by the United States would spell tragedy in the coming decade . The Yazidi mainly hoped for better access to water and gas after Saddam’s fall, and could not imagine the eventual outcome due to the instability of the region.

After many years of growing tension between the Yazidi people and those of Sunni communities, on August 3, 2014, the Yazidi were subjected to genocide by the Islamic State. The kidnappings and violence had been leading up to that day for years, but no one could have imagined what would happen. When the Kurdish forces exercised a tactical retreat, they left the vulnerable Yazidi communities exposed. Nadia lost 18 members of her family, and about 700 people were killed from her village alone on that day. Over 5000 men were killed and 5000-7000 women and children were abducted that month. Nadia and her family members were among the abducted.

From here Nadia takes the reader on her horrific journey where she, like thousands of other Yazidi women, were turned into sex slaves known as sabayas. Unlike other books which used graphic language to drive home just how terrifying and horrific the events were, Nadia does so through eloquence. Even though she transports us into the very rooms where the violent acts occurred, Nadia’s spirit and constant concern for others that drives the momentum forward.

After she recounts her escape and her current work as the United Nations Goodwill Ambassador for the Dignity of Survivors of Human Trafficking, Nadia mentions how outsiders focus on the constant sexual violence and rape that the Yazidi women and girls were subjected to. Personally, when speaking to others about this book, many tend to slowdown as if passing a gruesome traffic accident and sadly finding it entertaining. It is the consequences of the trauma that the Yazidi suffer to this day that she wishes to combat. This includes ongoing suicides, living in impoverished conditions in camps abroad, and the inability to return home. It is for this reason that we will not go into the specifics of what Ms. Murad and thousands of other women had to endure. Instead, we will focus on her harrowing escape, and her important work and how you can help. If you want to find out about the details of what Ms. Murad endured, buy a copy of the book and read it.

Nadia, like many others in her situation, attempted to escape more than once. The punishment for being caught while trying to escape is essentially the worst punishment possible. Many like her were subjected to these cruel and unthinkable acts by ISIS, and many were turned in by families who were afraid of what would happen to them if ISIS discovered that they aided a Yazidi woman in her escape attempt. On her last escape attempt, Nadia came to an Azawi family whose tribe had longstanding relationships with the Yazidi. They helped her escape but at a great cost. Nasser, the kind gentlemen who helped smuggle Nadia as his pretend wife was later killed for helping. At the camp within the Kurdish region of Iraq where Nadia stayed, she viewed how the trauma and the horror tore her people apart. As her nieces and cousins managed to escape, they shared their horrific experiences and looked to the future to build a new life. Not many could do this, sadly. For some, the anguish, pain, heartache, and ordeals they suffered under the hands of ISIS never stopped, and still go on.

What we can do to help

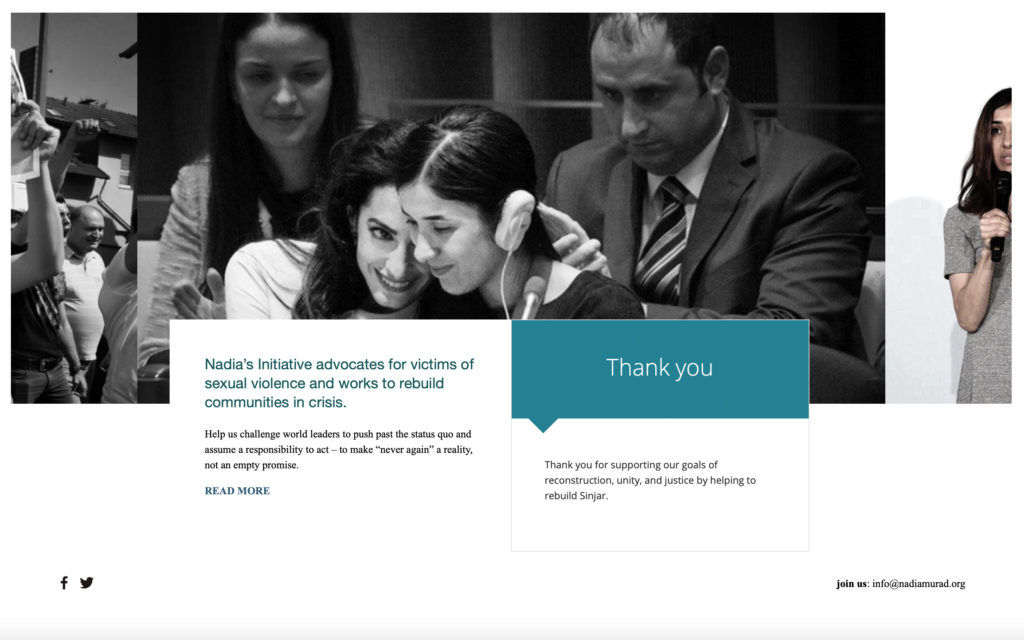

Nadia’s spirit and will to fight for her people is always persistent throughout the entire book, as it is now. She now works tirelessly with the United Nations to return her people to Sinjar,. Currently there are around 300,000 Yazidi living in camps in many countries. They are not receiving proper nutrition, or the education, healthcare, or psychiatric care needed.

Ms. Murad has started her own non-profit organisation called Nadia’s Initiative. Her efforts are the collection of donations and working with the Sinjar Action Fund to make the region of Sinjar once again habitable, and thus see her people return to their homeland. Northern Sinjar was liberated months after the siege, so the majority of the efforts are focused there. Southern Sinjar has been left ruined and riddled with land mines. As of the end of 2018, 15-20% of the Yazidi have returned to Sinjar. The agricultural sector was also purposefully destroyed by ISIS and recently a wildfire left the region in further despair. Basic infrastructure such as power, water, hospitals, markets, and schools, along with residential home repairs are also being worked on by the Sinjar Action Fund.

The unfortunate instability and ongoing crisis in the region continue to impede efforts in rebuilding Sinjar. The Kurdish government controls which roads and checkpoints are used, and this creates very difficult situations for the Yazidi on the ground to get the resources necessary to rebuild.

The key to making the rebuilding efforts of Sinjar a reality is that long-term and constant efforts need to be maintained by international aid organizations. Unfortunately in the past, humans have all been too eager to forget about genocides and to move on with their lives. This results in this important work not being accomplished.

Below is a link for more information, and for you to make a donation if you can. There is also a powerful movie made about Nadia’s efforts called On Her Shoulders. I highly recommend watching the movie after reading the book. A link to purchase a digital copy of the movie is also below.

http://www.onhershouldersfilm.com

At the end I will also provide a reading list covering similar topics of genocide, war, and how often in our history it happens. Hopefully by arming yourself with the knowledge in those books, you can better help those in desperate need in the future.

Conclusion:

In 2003, many residents in Canada became appalled for a second time at the Rwandan genocide which occurred nearly a decade earlier in 1994. This was due to the release of the book Shake Hands with the Devil: The Failure of Humanity in Rwanda by Roméo Dallaire whichdetailed what occurred in Rwanda and how the international community through knowing neglect failed the people of Rwanda. This second wave of shock and disgust however soon subsided after a film was made about it, even as Dallaire continued his work in trying to help Rwandans as the years passed.

The ability for us to brush aside the worst that we are capable of is astounding, and this keeps on happening. Many say that it is because we are overwhelmed by our own daily challenges and the constant fight to provide for our own families. I believe that it goes deeper than this, and unfortunately it is backed by ongoing observations.

Upon hearing about these tragedies, the genocides, the killings, the mass rapes, we are continually reduced to tears. These tears are temporary, however. Over the years since Dallaire’s book came out, I have observed many people in some form or another dehumanise other groups in some manner. They do this on the smallest of scales by muttering racial and ethnic slurs at bars, cafés, and restaurants when seeing a headline about a war from a distant land, or a crime within their own city. These acts of dehumanising others may seem benign, but they are not. In higher institutions of learning such as post-graduate business schools, medical schools, and law schools, there are divisions created between the minority student populations. This scales from simply not studying together, to not making eye contact throughout the entire duration of their degrees. This is further seen in elementary schools where parents divide each other based on race and in some cases do not allow their children to attend birthday parties and different social gatherings outside of the school. The overriding sense from those forcefully divided from these social groups and activities is a dark one. It is the message that their children are good enough to play with the children of the other group at recess, but they are not good enough to form long-lasting relationships and to potentially become lifelong partners and marry. I have observed this behaviour from lower-middle class neighbourhoods all the way up to the richest and most elite; I have heard this concern vocalised from a few parents.

Regardless of whether we think of ourselves as liberal, conservative, or indifferent, our tribal nature to think of others differently prevails. To do so on the smallest of scales allows for these genocidal events not only to be forgotten, but to happen time and again. To think of others as less than yourself in any way is to no longer consider them human, whether this be that they deserve the same rights and freedoms, or are inherently entitled towards employment and land. I have seen many unknowingly believe that other races are simply not capable of the same level of intelligence and empathy, or simply do not have the ability to experience events on the same plane as they do. People use opportunity as an excuse to view others as lacking the capacity to achieve what they can. When confronted by members of other races who have reached certain professional and societal milestones, often excuses and further explanations are given in private as to how this was possible to further justify their beliefs.

After reading this book and carefully observing those in Canada and the United States, it is my fear that this base tribalism that has been ingrained in us humans and has not been eradicated. It is my fear that it will persist and directly result in the lack of aid for such groups as the Yazidi in the long-term.

As a start, we need to get rid of this basic tendency to see others who do not share our background as lesser than us. Otherwise, these genocides will continue to happen in regions where people have nothing to lose, and where many need to turn their aggression and violence somewhere to explain their hardships and perceived injustices.

Reading this last section of this book review may have been difficult for you, and you may not have experienced this form of discrimination personally, or think that it still manifests itself in our society. If you are in this camp, consider yourself fortunate. Those who went through the most horrific experiences and crimes possible need our help. Instead of buying the fifteenth watch strap for your watch, for example, maybe put that money towards helping build a better future for those whose lives, cultures, and collective potential have been systematically destroyed in the most dreadful manner imaginable. I have started doing this, and I hope that you do so as well on occasion.

Reading such books as the important work by Nadia Murad and those listed below, is essential in making sure that we will not continue to forget the atrocities that our most vulnerable suffer, and to help those who need it the most in the future.

Most importantly, choose not to forget. Choose to keep yourself informed, and act if you can.

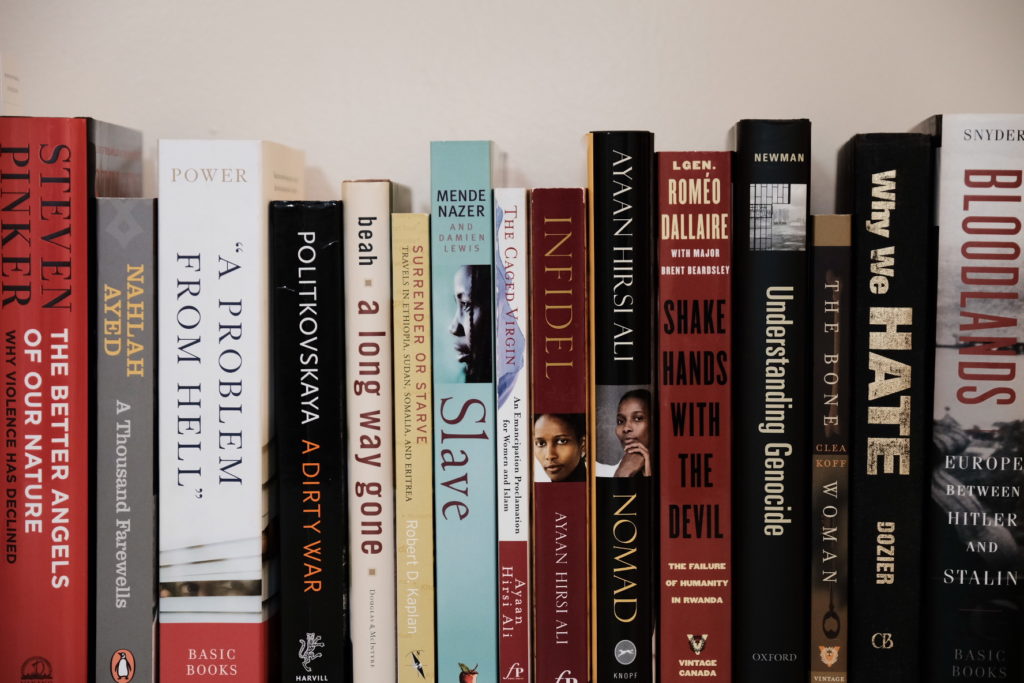

Further Recommenced Reading:

- “A Problem From Hell” by Samantha Power

- “A Thousand Farewells” by Nahlah Ayed

- “The Beekeeper” by Dunya Mikhail

- “A Moonless Starless Sky” by Alexis Okeowo

- “Shake Hands with the Devil” by Roméo Dallaire

- “A Dirty War” by Anna Politkovskaya

- “A Long Way Home” by Ismael Beah

- “Surrender Or Starve” by Robert D. Kaplan

- “Slave” by Mende Nazer

- “The Caged Virgin” by Ayaan Hirsi Ali

- “Infidel” by Ayaan Hirsi Ali

- “Nomad” by Ayaan Hirsi Ali

- “The Bone Woman” by Clea Koff

- “Understanding Genocide” edited by Leonard S. Newman & Ralph Erber

- “Why We Hate” by Rush W. Dozier Jr.

- “Bloodlands” by Timothy Snyder

- “The Better Angels of Our Nature” by Stephen Pinker