(880 words)

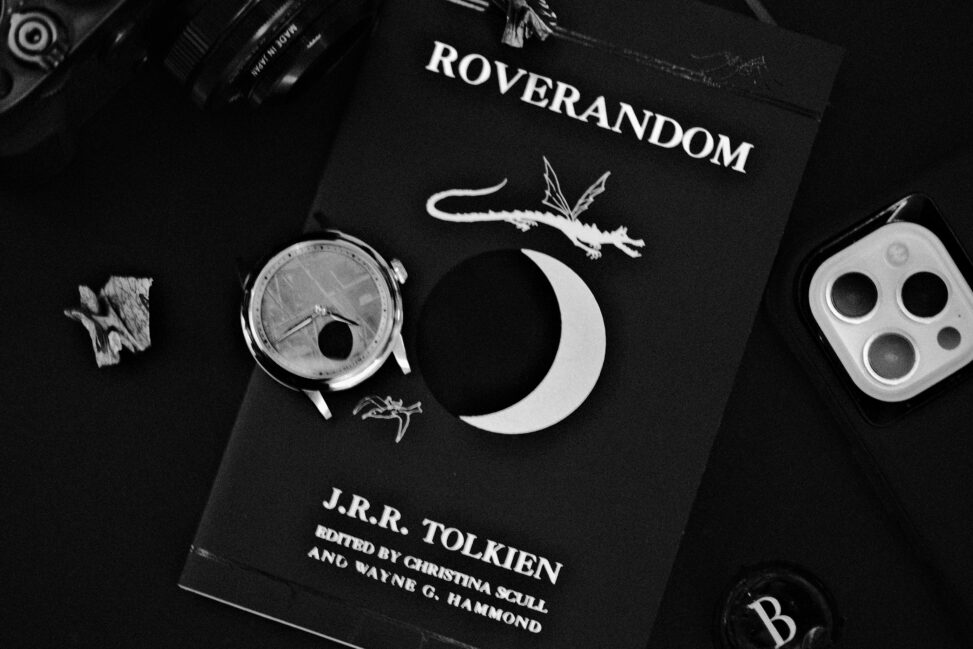

As the end of this work week arrived, I had the rare fortune of having a soft landing on a Friday night before meeting friends for dinner. As I entered the café next to the restaurant an hour early, all was looking good. A promising café with delightful Turkish pastries and coffee, plenty of vacant seating, and a happy group running the place consisting of the owner and her attentive and caring do-it-all barista. Excited, I ordered enough coffee and pastries for a small family, and I settled in to starting not one, but two books. One focused on the dark, dense, and dispiriting history of the middle east from the 1960s until now, while the other was a children’s book written by J.R.R. Tolkien for his own children while on vacation.

Feelings of warmth radiated within me from the cardamom infused coffee, a shambali which was so light that it could have easily lifted me into orbit, and the introduction to Tolkien’s work, Roveradom, written by Christina Scull and Wayne G. Hammond. The details of how as a loving father, Tolkien wrote an elaborate story about his son’s lost toy dog reminded me of every parent I had observed as they cushioned the blow of reality for their beloved child. To be honest, there is nothing more magical than seeing a child being slowly consoled and comforted by the guidance and care of a parent who is pouring every ounce of their soul into their child’s wellbeing.

What followed, outside of the pages of the book in my hands, could not have been scripted as to provide a trenchant contrast. A man well into his eighties claimed the table next to me by tossing his pristine leather gloves on top of the menu, followed by his daughter who was in her early fifties. The first thing that struck me was how beautiful they both were. This was the kind of effortless beauty that ensures a much smoother and paved road on the journey of one’s’ life. The second thing which hit me was the silence between the two.

As they eventually settled, the father ordering his favourite apple turnover and a decaf latte, and the daughter defiantly ordering nothing, the silence bloomed into something unexpected and unbearable.

The next twenty minutes consisted of the father trying to engage in a conversation with his daughter whom he sees once a week, only to be shut down every time. Endless complaints and criticisms poured from the frustrated daughter as her body language violently throbbed like a pulsar desperately caught within the grasp of a yet to be seen intermediate black hole.

Every frenzied burst was met with an inward sigh from the father as his eye contact broke off into the expertly crafted soft landscape of his latte. His eyes sent out a gravitational ripple of exhaustion. Yet the fatigue stood no hope in deteriorating his decade’s long duty in safeguarding his daughter as she navigated the world while suffering from a severe horde of pathologies.

As the minutes went by, his daughter’s body language turned more aggressive, but I started observing signs of the onset of dementia for the father as he repeated two specific questions, only once. His daughter launched in frustration to his plea for her to order something, and of how her transition back to life was from her vacation.

This instantly broke my heart. Newspapers, magazines and journals are flooded with middle aged, read working age, authors writing about the challenges of having to take care of their aging parents with various forms of dementia and quality of life issues. I even wrote an immense guidebook on how to do this here. In all of my hours of reading a day, I have never come across an article written from the point of view from someone who is facing dementia like a speeding vehicle in their rearview mirror, while also having to still nurture and provide for their adult child which they deeply love. As someone who for a multitude of reasons is childless, all for the hypothetical child’s benefit mind you, I have gone through great measures in making the lives of those in my life who are parents easier. But so much of the focus, both in literature and that of real life, has been on the time-sink that a normal child or one with developmental disorders can be, or that of a parent who is suffering from dementia.

As I looked on to my notebook in front of me as I tried to take notes on what I was reading, I met the eyes of the father in the mirror on the wall in front of us as I raised my head. We shared a look of soft, yet narrow eyes followed by a nod. His quiet strength was worn, but not defeated, but I could not help but be staggered at the range of experiences we humans are afforded as the night went on. From reading about functional and loving families, to meeting and embracing joyful friends who did nothing but share bursts of laughter and understanding, the father’s quiet eyes never left my side.

Though we all have hard lives with our own never-ending series of challenges and episodes of heartbreak, nothing, outside of living within a combat zone, compares to those carrying the weight of a broken person for three quarters of their lives.